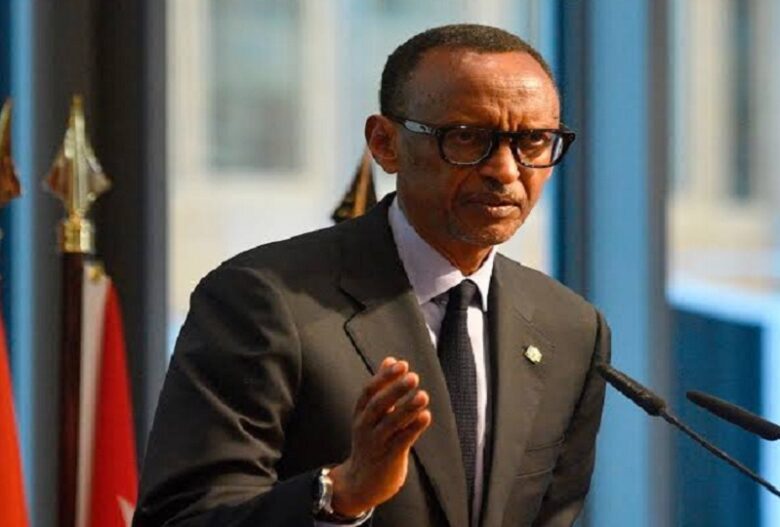

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame faces little room for improvement in Monday’s election, having previously secured nearly 99% of the vote. His overwhelming victories, with 95% in 2003 and 93% in 2010, have raised questions about the democratic nature of these elections. However, the former refugee and rebel leader confidently dismisses such criticisms.

Kagame dismisses the critiques with confidence. “There are those who think 100% is not democracy,” he remarked to thousands of cheering supporters at a campaign rally in western Rwanda last month.

Without naming specific countries, he added, “Many leaders are elected with just 15%, Is that democracy? How?” Kagame asserted that Rwanda’s affairs are its own concern.

His supporters echoed his sentiments, chanting “they should come and learn” while waving the red, white, and sky-blue flags of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) party.

Towering over the crowds at over 6ft (1.83m), the wiry 66-year-old father of four exudes a stern and commanding presence.

Though he occasionally cracks a smile and a joke, the bespectacled leader frequently bears the expression of a disapproving elder.

His calm, reflective manner compels attention, and when he speaks, he tends to be straightforward, rarely softening his words.

Whenever he opts for more vague or diplomatic expressions, he often utilises insinuation to convey his message clearly.

The conflict between Rwanda’s Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups has significantly shaped Mr. Kagame’s life.

To move past this historical division, his administration advocates for a national identity that emphasises being Rwandan over ethnic distinctions.

Election Context

In office since 2000, President Kagame is campaigning for a fourth term, but he has effectively been the leader of Rwanda since July 1994, when his rebel forces overthrew the Hutu extremist regime responsible for that year’s genocide.

He first held positions as vice president and defense minister.

Numerous supporters, including prominent Western politicians, commend him for restoring stability and rebuilding Rwanda following the mass slaughter of 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

While some critics allege that his rebel forces engaged in revenge killings during that period, his administration maintains that these were isolated incidents, and those responsible were held accountable.

Outspoken in his critiques of the West, the president also seeks support by emphasizing the moral responsibility for the failure to intervene during the genocide.

Political Landscape

Rwanda participated in a now-abandoned UK initiative designed to transfer asylum seekers to the country, which offered financial benefits.

“I’m definitely voting for PK,” university student Marie Jeanne states, referring to Mr. Kagame by his initials.

“You can see how well I’m studying. Without his presidency, I might struggle due to insecurity,” she shares with the BBC.

The decision of whom to support was straightforward for her. She firmly believes in President Kagame’s leadership and the stability it has brought to the country.

However, there are two other candidates on the ballot for the nine million registered voters. Frank Habineza from the Democratic Green Party and independent Philippe Mpayimana are also in the race.

This election mirrors the presidential contest from seven years ago, with both challengers hoping to make an impact against Kagame’s long-standing administration.

In the last election, the Democratic Green Party’s Frank Habineza and independent Philippe Mpayimana received just over 1% of the total votes between them.

This marks a continuation of their challenge from the previous presidential election, where they struggled to gain significant support against Kagame’s overwhelming popularity.

Meanwhile, other political parties have rallied behind President Kagame, further solidifying his position as the leading candidate.

His long tenure and the stability he has brought to Rwanda have garnered him a substantial base of support among voters.

In contrast, opposition politician Diane Rwigara, a vocal critic of Kagame, was barred from running due to alleged paperwork issues.

She has dismissed these claims as an excuse designed to thwart her candidacy and suppress dissent within the political landscape.

Accusations against Mr. Kagame include suppressing dissent by imprisoning and intimidating political opponents.

In a past interview with Al Jazeera, he stated that he should not be held accountable for the lack of a robust opposition.

Additionally, there are claims that his extensive intelligence network has been involved in various cross-border assassinations and abductions.

Col. Patrick Karegeya, a former intelligence chief who had a falling out with Mr. Kagame and subsequently fled Rwanda, is believed to have been targeted by their network.

In 2014, he was killed in his hotel suite in Johannesburg, South Africa.

David Batenga, Col Karegeya’s nephew, recounted, “They literally used a rope to hang him tight.”

While officially denying any involvement, Mr. Kagame did little to distance himself from the killing.

At a prayer meeting shortly after, he remarked, “You can’t betray Rwanda and not get punished for it.

Anyone, even those still alive, will face the consequences. Anyone. It is just a matter of time.”

Kagame’s efforts to ensure security domestically have led to the deployment of troops into the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, under the pretext of targeting a Hutu rebel group.

Despite significant evidence, including a recent UN report, Rwanda denies allegations of backing the M23 rebel group there.

“Honestly, the election is a farce,” says Filip Reyntjens, a Belgian political scientist specializing in the Great Lakes region.

Reflecting on the upcoming poll, he adds, “I don’t know what will happen this time, but previous elections have been a circus.”

“The national electoral commission attributes votes rather than counting them,” citing the last European Union (EU) observer mission report from 2003 and the Commonwealth observer mission report from 2010, He alleged.

The electoral commission of Rwanda claims on its website that it ensures “free, fair, and transparent elections to improve democracy and boost adequate governance in the country.”

“From my perspective, the forthcoming presidential election in Rwanda is inconsequential,” remarks Dr. Joseph Sebarenzi, a former speaker of the Rwandan parliament.

Having lost both parents and numerous family members during the genocide, he brings a deeply personal understanding of the country’s political landscape.

Now residing in exile in the United States, Sebarenzi emphasizes the lack of genuine democratic processes in the nation.

“The election resembles a football match where the organizer is also a player, chooses the other participants, instructs people to attend, and where the outcome is already known, yet everyone must act as if the match is genuine.”

Historical Background

A passionate football fan and dedicated supporter of Arsenal in the English Premier League, Mr. Kagame would probably challenge this portrayal.

Raised in a well-off family in central Rwanda in 1957, he was the youngest of five children.

However, his childhood was marked by upheaval, as he fled to neighboring Uganda with his family at the age of two, escaping the targeted violence against the Tutsi minority during the late 1950s.

Even as an infant, Mr. Kagame has recounted memories of witnessing the devastation around him, stating, “I remember looking out toward the next hill, where we could see people setting houses on fire.”

“They were killing people. My mother was in despair; she didn’t want to leave this place,” the president shared with American journalist and unofficial biographer Stephen Kinzer.

The unrest began when Belgian colonizers shifted their support to the majority Hutu ethnic group, which had faced discrimination under the Tutsi monarchy. Rwanda achieved independence in 1962.

During the late 1970s, Mr. Kagame undertook several covert trips back to Rwanda. In Kigali, he often visited a hotel in Kiyovu, one of the city’s affluent areas.

The bar there was a gathering spot for politicians, security officials, and civil servants, who exchanged gossip over drinks after a long day.

According to Mr. Kinzer, the future leader would sit discreetly at a table, sipping an orange soda while eavesdropping on the conversations of politicians, security officials, and civil servants.

These trips to Rwanda heightened his interest in the tactics of espionage.

He received military intelligence training in Uganda and participated in the successful rebellion led by Yoweri Museveni, who took power in 1986.

Mr. Kagame also trained in Tanzania, Cuba, and the United States. Subsequently, he led his predominantly Tutsi rebel army into Rwanda in 1990.

“The training proved valuable. Cuba, given its confrontations with the US and its relationship with Russia, had developed sophisticated intelligence methods.

“Additionally, there was an emphasis on political education: What is the essence of the struggle? How do you maintain it?” he conveyed to Mr. Kinzer.

Future Prospects

Mr. Kagame has focused on economic growth as a means to sustain progress, suggesting that Rwanda could model itself after Singapore or South Korea and attain substantial development within a single generation.

While Rwanda did not reach its middle-income country goal by 2020, Professor Reyntjens asserts that “this is a well-managed country”.

He emphasizes, however, that the challenge lies in political governance, noting the absence of a level playing field, limited space for opposition, and a lack of freedom of speech, which threatens to undermine the successes of effective administrative governance.

However, Mr. Kagame argues that the large crowds at his rallies demonstrate the trust and affection Rwandans have for him and their desire for his continued leadership.

Despite previously stating he would have groomed a successor by 2017, he remains confident in the support of the Rwandan people.

Due to constitutional changes, he could theoretically stay in power until 2034.

Last month, in a live interview on the state broadcaster, Mr. Kagame emphasized that “the context of every country” matters when addressing the issue of his extended tenure.

Addressing the issue of his prolonged tenure, he stated, “The West says, ‘Oh, you have been there too long.’ But that’s none of your business. It’s the business of these people here.”

From his vantage point in the US, Dr. Sebarenzi, who fondly calls Rwanda the land of a thousand hills, expresses uncertainty about its future.

“History shows that in countries where the leader wields greater authority than the institutions, power transitions can lead to violence and chaotic aftermaths once the regime falls,” he remarked.

YOU MAY ALSO READ: Suspected smuggler kills customs officer while trying to escape arrest in Northern Nigeria

Got a Question?

Find us on Socials or Contact us and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible.