In the scorching capital of N’Djamena, Chad, housewife Sylvie Belrangar found herself unable to access water despite turning the tap handle, as water shortages and extreme temperatures grip parts of West and North-Central Africa’s Sahel region.

“The president promised water and electricity. But since then, we’ve seen nothing,” she lamented last week, surrounded by withered plants in her dry compound.

Belrangar’s predicament is mirrored elsewhere in the semi-arid Sahel, where the most severe heatwave in recent memory, experienced in April, highlighted the challenges faced by junta-led countries like Chad and Mali in ensuring basic services during periods of heightened demand for water and electricity.

Recent power outages have fuelled discontent among segments of the population in Mali and Chad, heightening social tensions at a pivotal moment in both countries’ political trajectories.

In Chad, an upcoming presidential election scheduled for Monday is anticipated to solidify Mahamat Idriss Deby’s hold on power, following his two-year tenure since his father’s passing.

Critics argue that the election is merely a facade to validate Deby’s leadership and will not accurately represent the sentiments of voters like Belrangar, who have grown disillusioned with Deby’s governance.

“We have a president who can’t even provide water and electricity, let alone anything else,” she said. “Let the authorities listen to our cries.”

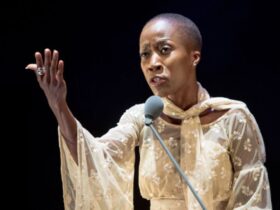

In Mali’s capital city of Bamako, Ice vendor Bintou Traore took measures to protect her diminishing ice supply from the sun by covering it with blankets on Tuesday.

“Ice is very expensive now,” she remarked. “At the factory, prices have gone up because the plants run on generators.”

The April heatwave resulted in a significant increase in excess deaths at Bamako’s Gabriel Toure Hospital, with climate scientists estimating thousands of additional casualties across the region.

Ensuring a stable power supply is crucial in mitigating the repercussions of extreme heat, as it allows for the continuous operation of fans, air-conditioners, and refrigeration units.

Despite repeated requests for comment, officials from the governments of Chad and Mali have not provided a response.

The increase in electricity outages in Mali since the military took control in a 2020 coup has significantly impacted public support for the junta, especially during periods of rising temperatures and resulting hardships, noted political analyst Koureissi Cisse.

“People outside are having seizures and strokes. People are dying… because of the heat, but also lack of electricity,” he remarked.

Opposition leaders have cited the power cuts as evidence of the junta’s inadequate governance, particularly as the authorities continue to postpone the promised transition to democracy and impose restrictions on political activities under the guise of maintaining public order.

YOU MAY ALSO READ: Devastating rainfall causes death toll to rise to 29 in southern Brazil

Got a Question?

Find us on Socials or Contact us and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible.